Monday, February 27th, 2012

Virtually nothing is known of this abandoned cemetery in Picacho, even by residents. The cemetery is on private land. Only two stones exist, but mounds and other signs indicate other burials.

See also:

Picacho Peak

Picacho — A Brief History

Picacho — Forgotten Butterfield Stage Stop

Tags: History, Mesilla, Stage Coach, Butterfield Overland Mail

Tuesday, February 14th, 2012

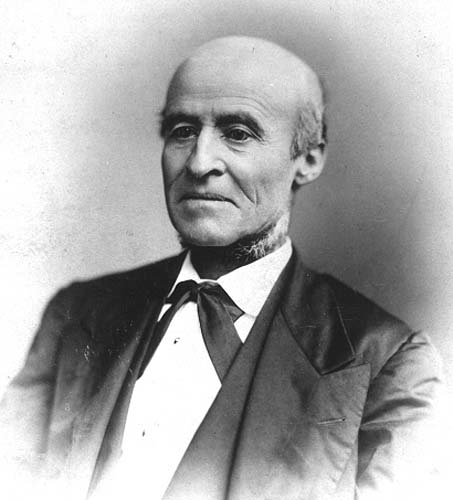

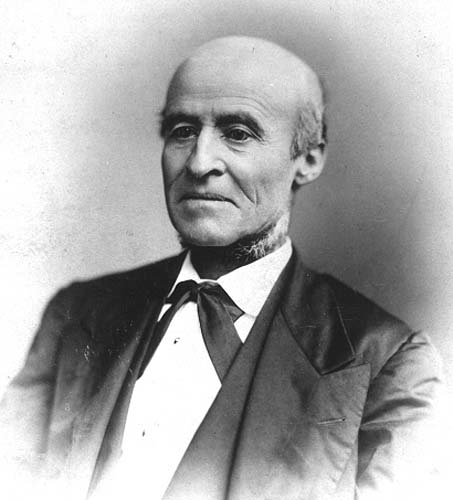

Evangelisto Chavez

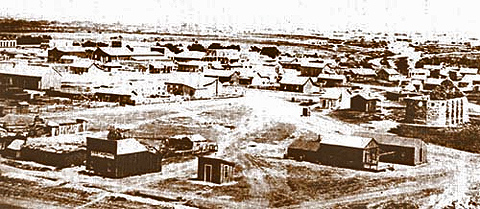

Picacho was founded in 1855 by Juan (or Jose) Evangelisto Chaves, known as Evangelisto Chaves. Evangelisto, born May 8, 1827, had moved to Mesilla from Socorro, New Mexico some time before 1855. Evangelisto’s family history goes back to Pedro Gomez Duran Y Chaves*, who was born in Valverde de Llerena, Spain, and was one of the founding residents of Santa Fe in 1602. Evangelisto married Maria Petra de Jesus Trujillo in Socorro in 1851.

Picacho had long been a camping spot because it was located just south of a natural Rio Grande River crossing known as Apache or Indian Ford. It was also near one of the few places where it was possible to get wagons or coaches up the western slope of the Mesilla Valley. Even though the valley is not that steep, the west side consists of deep sand that provides a formidable barrier to horse-drawn conveyances.

Local tradition says that Evangelisto built the first house in Picacho. He established a large farm and a mercantile business and began employing many workers. He also started a ferry boat service at Apache Ford. Because he owned almost the entire town, it was sometimes called Chaves.

With Evangelisto’s financial acumen and the business provided by the Overland Mail Stage Stop established in 1858, the settlement grew fast. Just how fast can be seen in an 1859 Territorial vote:

Dona Ana, 240

Las Cruces, 100

Brazito, 19

La Mesa, 212

Santo Tomas, 69

Mesilla, 1101

Picacho, 136

Tucson, 267

Colorado City (Rodey), 100

These numbers are votes, i.e., United States male citizens, but they give an idea of the relative populations of the towns of southern New Mexico at this time (Arizona was part of New Mexico until February 24, 1863).

Picacho’s close proximity to the mountains made it vulnerable to Indian attacks, and there are accounts of raids in which livestock were taken and citizens lost their lives. Here is a typical account:

“On the morning of the 30th ult., five Apaches stole out of a corral at the village of Picacho, two hundred head of cattle. To show the audacity of these Indians, we will note that the stock was stolen within five miles of a camp of 650 soldiers.” (September 30, 1861)

During the Civil War, Picacho’s position as a transit point to Arizona led to its use for that purpose by both Confederate and Union troops.

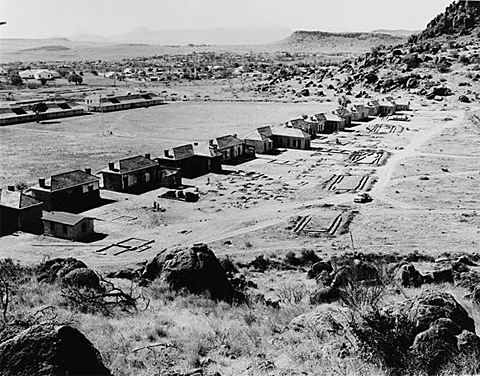

With the arrival of the train at Las Cruces in 1881, Picacho along with Mesilla, La Mesa, Dona Ana, and Santo Tomas began a decline that led, by 1900, to almost insignificance.

Evangelisto, who is enumerated in the census of 1880 as living in Picacho, recognized Picacho’s dwindling importance and moved to Las Cruces in July, 1881, where he built a large house. In Las Cruces he had many business interests and served as Justice of the Peace, county treasurer, and school commissioner. He died unexpectedly on March 2, 1886.

*Although about 250 Spanish men and a few wives settled in Santa Fe following Don Juan de Oñate’s expedition there in 1598, by 1608 only about 50 remained, of which Pedro Gomez Duran Y Chaves was one. He was appointed Military Commander of New Mexico in 1627. His descendents spell the name both Chavas and Chavez.

See also:

Picacho Cemetery

Picacho Peak

Picacho — Forgotten Butterfield Stage Stop

Rough and Ready – Butterfield Stage Stop

Sources:

Research by Dan Aranda; Photo of Evangelisto Chaves Copyright 2012 Dan Aranda; “Santa Fe Weekly Gazette,” January 8, 1859; “The Daily Dispatch,” November 5, 1861; “Rio Grande Republican,” March 6, 1886; Chavez, A Distinctive American Clan of New Mexico, by Fray Angelico Chavez.

Tags: History, Mesilla, Stage Coach, Butterfield Overland Mail

Thursday, October 27th, 2011

Many who have written about the Butterfield Overland Mail have left out the Picacho stage stop, sometimes called Rancho Picacho, in their accounts. This is a bit surprising as the very first written account of the Butterfield trail mentions the Picacho stop.

Waterman Lilly Ormsby, a special correspondent for the New York Herald, took the first stage from St. Louis to San Francisco so he could report on the experience. He was the only passenger with a straight-through ticket. He left St. Louis on September 16, 1858 and arrived in San Francisco 24 days later, the stage having traveled day and night, stopping so passengers could sleep only every second or third night.

During the trip Ormsby wrote 8 articles about the trip, which were published in the Herald.

Mesilla was almost exactly half way between St. Louis and San Francisco.

Here is what Ormsby wrote on leaving Mesilla:

“A few miles from Messilla [Mesilla] we changed our horses for another team of those interminable mules, and started on a dreary ride of 52 miles for Cook’s Spring. This is the commencement of that series of deserts without water extending from the Rio Grande to the Gila – one of the most tedious portions of the route.

Our road lay through what was called the Pecatch [Picacho] Pass, and, as I walked nearly all the way through it, it seemed to me rather mountainous. It was about 2 miles long and had some very bad hills. In comparison with other passes and canyons on the route, it was not very bad, though quite bad enough and all uphill. When, however, we reached the summit, we were upon the border of a broad and level plain extending as far away as the eye could reach. At our backs were the ranges of the Oregon [Organ] Mountains, the debris of the Rocky Mountains, forming the Eastern boundary of the Messilla [Mesilla] Valley. In front we could just see in the distance Cooke’s peak, rising from the plain in bold prominence from among the surrounding hills.”

The stop where the stage changed from horses to mules was the Picacho stop. Mules were used when the road was rough and mountainous. Mules could handle rougher terrain, but were slower than horses, so the Picacho stop was important, else mules would have had to be put on in Mesilla, making it a tough pull to reach the first stage stop after Picacho, Rough and Ready.

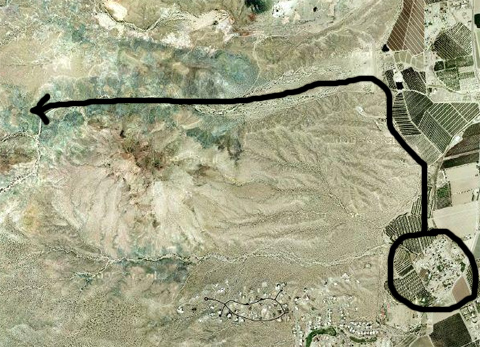

As noted in this post and confirmed by the Ormsby quote above, the stage went north of Picacho peak, not south as almost all writers have it. There was a southern road that stayed on the plains, which horse riders often took, but the water necessary for animals pulling a stage was available only on the mountainous route.

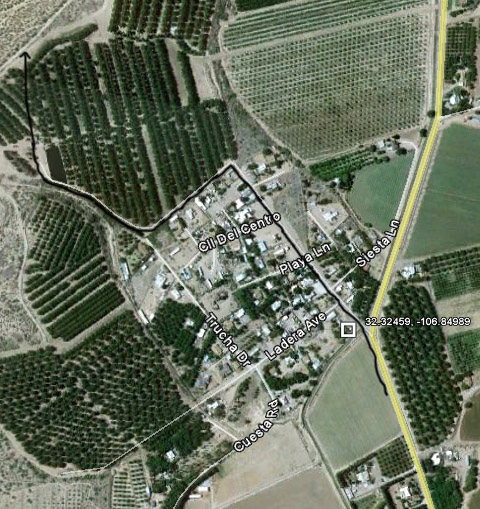

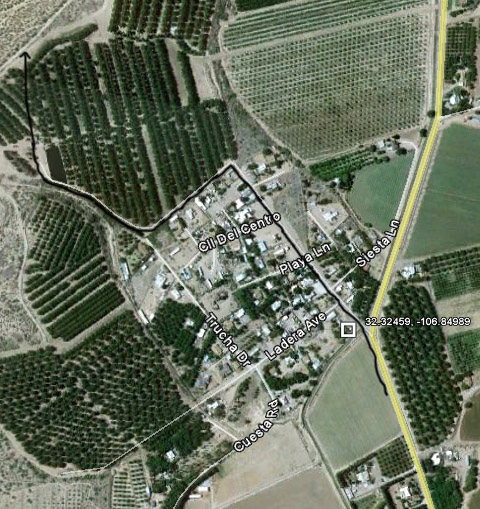

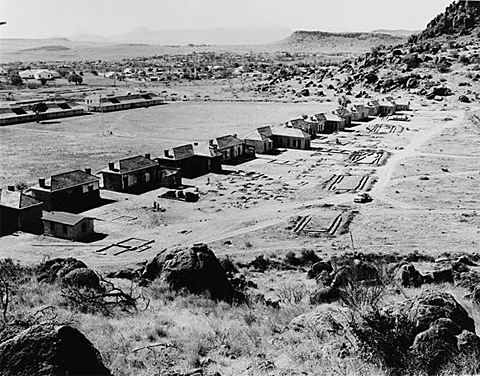

The last remains of the stage stop in Picacho were torn down in 1954, but here is the location today in the old village of Picacho:

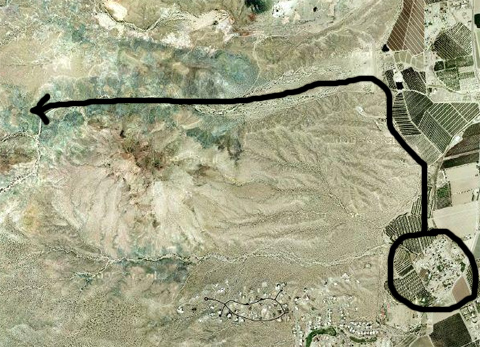

Below is a Google satellite image with the location of the Picacho station marked (white square). The GPS is 32.32459, -106.84989. The black line shows the route the stage took through Picacho.

Here is an old adobe in Picacho probably built in the 1890s.

See also:

Picacho Cemetery

Picacho — A Brief History

Picacho Peak

Rough and Ready — Butterfield Stage Stop

Trip to Mason’s Ranch

Stage Coach from Mesilla – Unfulfilled Promise

Mesilla Stage Coach – More

Tags: History, Mesilla, Stage Coach, Butterfield Overland Mail

Monday, August 8th, 2011

As noted in the post Colt’s Six-Shooters at 15 Paces, Jose Manuel Gallegos and Judge John S. Watts fought a duel “near the Mexican line” on September 10, 1859. Neither man was injured, although they each fired five bullets using what were then advanced, modern weapons.

Why did they choose to fight “near the Mexican line?”

They did so because the legal sanctions against dueling in New Mexico at the time were severe.

Section 20 of Chapter 11 of the Territorial laws in 1859 stated:

“Every person who shall by previous engagement or appointment fight a duel within the jurisdiction of this Territory, and in so doing shall inflict a wound upon any person, whereof the person so injured shall die, shall be deemed guilty of murder in the second degree.”

The punishment provided in the same statues for second degree murder if premeditation was involved was life in prison.

It was also against the law to fight a duel even if no one was wounded or killed:

“Every person who shall engage in a duel with any deadly weapon, although no homicide ensues, or shall challenge another to fight such duel, or shall send or deliver any written or verbal message purporting or intending to be such challenge, although no duel ensues, shall be punished by imprisonment in the county jail or territorial prison not less than one year, or shall be fined in any sum not leas than two hundred dollars nor more than one thousand dollars.”

But it wasn’t just duelers who faced extreme legal liability. Their seconds also could be charged with murder:

“Every person who shall be the second of either party in such duel as is mentioned in the preceding section, and shall be present when such wound shall be inflicted, whereof death shall ensue, shall be deemed to be an accessory before the fact to the crime of murder in the fifth degree.”

The strict provisions of the law intended to prevent dueling didn’t end there, however. Both the act of issuing and accepting a challenge were illegal:

“Every person who shall engage in a duel with any deadly weapon, although no homicide ensues, or shall challenge another to fight such duel, or shall send or deliver any written or verbal message purporting or intending to be such challenge, although no duel ensues, shall be punished by imprisonment in the county jail or territorial prison not less than one year, or shall be fined in any sum not leas than two hundred dollars nor more than one thousand dollars.”

“Every person who shall accept such challenge, or who shall knowingly carry or deliver any such challenge or message, whether a duel ensues or not; and every person who shall be present at the fighting of a duel with deadly weapons, as an aid, or second, or surgeon, or who shall advise, or encourage, or promote such duel, shall pay a fine of not less than five hundred dollars, nor more than one thousand dollars.”

See also:

Colt’s Six Shooters at 15 Paces

Tags: History, Mesilla

Monday, February 1st, 2010

Picacho Peak, 4959 feet, about 7 miles from Las Cruces. (Click for a larger image.)

The old village of Picacho is located southeast of the peak, at the edge of the Mesilla Valley. Picacho was a stage stop on the Butterfield Overland Stage Line , the first stop after Mesilla. From Picacho, the stage climbed the mesa and went around the north side of Picacho Peak through Box Canyon. This lead to a very difficult route through several mountain ranges, but was the only route on which water could be supplied at the stage stops, which were located about one hour of travel time apart.

From Mesilla the stage stops to the Arizona border were: Picacho, Rough and Ready, Goodsight, Cooke’s Springs, Mimbres, Cow Springs, Soldiers’s Farewell, Barney’s, Steins Peak.

The Butterfield Stage began operation on September 15, 1858, with stages leaving San Francisco and St. Louis, the two ends of the line, on that day. Mesilla was located about the middle of the route.

The Butterfield Stage was put out of operation by the start of the Civil War.

See also:

Picacho Cemetery

Picacho — A Brief History

Picacho — Forgotten Butterfield Stage Stop

Rough and Ready — Butterfield Stage Stop

Stage Coach from Mesilla – Unfulfilled Promise

Mesilla Stage Coach – More

Tags: History, Mesilla, Stage Coach, Butterfield Overland Mail

Saturday, January 16th, 2010

DUEL NEAR MESILLA — Correspondence dated Mesilla, 10th September, says:

On Sunday (4th September) Otero, the Democratic nominee for Delegate from New Mexico, made a speech in the Plaza in this town. He was answered by Judge [John S.] Watts, a Galligos [Gallegos] stumper. In the course of his remarks he made allusion to the family of Otero in such a manner that Otero gave him the lie. A challenge ensued, and the parties, accompanied by their seconds, surgeons, etc., met yesterday morning, near the Mexican line. Three shots were exchanged. Weapons, Colt’s navy six-shooters; distance, fifteen paces.

After the first fire the seconds endeavored to effect a reconciliation, but were unable to do so. Two more shots were exchanged without effect, when the seconds withdrew their principals from the field. The difficulty still remains unsettled, however. Both parties behaved with especial gallantry and coolness. After the second shot, Otero lighted his cigarito and enjoyed his smoke, while Watts amused himself with whistling.

Source: Sacramento Daily Union (newspaper), October 5, 1859

In the election referred to in this article, Delegate from New Mexico to the legislature of the United States, Jose Manuel Gallegos was defeated by Miguel Antonio Otero. This was a continuation of a very personal political war between the two men that begin in 1855.

Gallegos and Otero dominated early New Mexico politics.

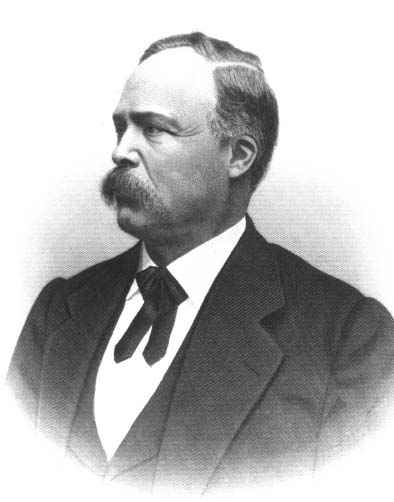

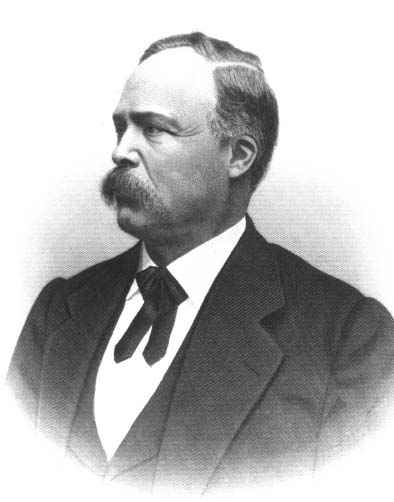

Jose Manuel Gallegos

Gallegos was born in New Mexico in 1815 while it was still part of Mexico and was ordained as a Roman Catholic priest in 1840. When New Mexico became a territory of the United States as a result of the Mexican-American war, Gallegos participated in the planning of a plot to revolt against American authorities and restore New Mexico to Mexican control. As a result of that activity and other conflicts with the Catholic Church, Bishop Jean Baptiste Lamy forced Gallegos’ resignation from the priesthood in 1846.

Always very political, Gallegos had served in the Department of New Mexico Assembly under Mexican rule from 1843 to 1846. Even though he opposed American rule following the Mexican-American war, he evidently decided that if you can’t beat them, join them. Gallegos was elected to the American New Mexico Territorial Council in 1851, and then won election as the Territory’s Delegate to the US Congress in 1853.

In 1855, Gallegos ran against Otero for the first time, and won a second term as Delegate. But Otero alleged massive voter fraud in Mesilla and he eventually prevailed, due primarily to his party’s control of the certification process. Gallegos was forced to give up his position several months before his term ended, and Otero replaced him.

Miguel Antonio Otero

So the 1859 election contest between Gallegos and Otero was a blood match between two men who heartily despised each other. Adding to the open bitterness of the conflict, Bishop Lamy strongly supported Otero, making the election a continuation of his old feud with Gallegos.

After Gallegos lost as Delegate in 1859, he won election to the New Mexico Territorial legislature in 1860 and served as Speaker of the House.

Gallegos failed again as Delegate candidate in 1862, but in 1871, after switching to the Democratic Party, he succeeded in defeating J. Francisco Chaves and becoming Delegate for a third time.

The Gallegos/Chavez contest was the cause of the Mesilla Riot, August 27, 1871, which resulted in at least seven deaths and 30 woundings. More on the Mesilla Riot in a later posting.

Gallegos died April 21, 1875 and is buried in the Rosario Cemetery in Santa Fe.

See Also:

Mesilla Duel — Legal Considerations

Sources:

Hispanic Americans in Congress, Carmen E. Enciso and Tracy North, 1996.

History of New Mexico: From the Spanish Conquest to the Present Time, Helen Haines, 1891.

The Leading Facts of New Mexican History, Ralph Emerson Twitchell, 1917.

Tags: History, Mesilla

Wednesday, September 30th, 2009

Are ready and are being picked.

Many say the best chiles in the world come from Hatch.

Don’t believe it. The best chiles come from Mesilla.

Tags: Chiles, Chile Rellenos, Peppers

Saturday, June 6th, 2009

Tags: Misc Images

Tuesday, March 10th, 2009

As noted in this prior post, Stage Coach from Mesilla – Unfulfilled Promise, Louis Cardis had just established a stage coach line from Mesilla to San Antonio/Austin, with rail connections to St. Louis, when he was murdered.

Cardis’ line was called The Texas & California Stage Company. As shown in this, his first of only two advertisements, his line used four-horse coaches.

The one-way cost from Mesilla to St. Louis, which included the train fare, was $107.50. It’s interesting that it was not rounded either up or down.

Mesilla Valley Independent (newspaper), October 13, 1877

His Way Table from the same issue shows the stops from Mesilla to Fort Concho. The average distance between stops is about 30 miles. At each stop the horses would be changed. If the stage broke down between stops, the plan would have been to unsaddle a horse and ride to the nearest stop to obtain what was necessary to repair the coach.

Time was important even in that age. That is why the stage rode night and day for several days before pausing to permit the passengers to sleep a little. Hotel or sleep accommodation charges were not included in the fare.

Meals were available at each stop for 50 cents.

Mesilla Valley Independent (newspaper), October 13, 1877

Tags: History, Mesilla, Stage Coach

Friday, March 6th, 2009

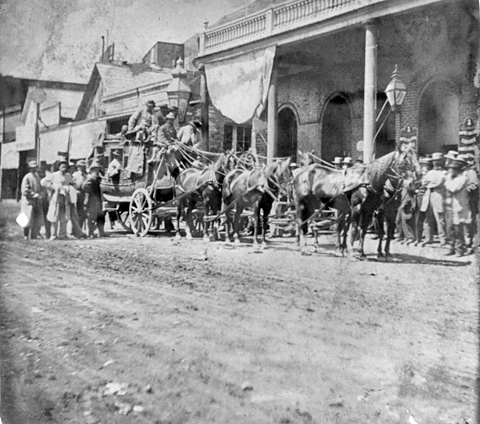

Stage Leaving Town – Library of Congress Photo

“Hon. Louis Cardis of El Paso was in town during the early part of the week completing arrangements for starting a line of coaches between Mesilla and El Paso. This line fills the break and gives us a through line of coaches from San Diego, Cal., to San Antonio and Austin Texas. Mr. Cardis is the proprietor of the line of coaches running from El Paso to Fort Davis Texas, from which point there is close connection with other lines of coaches that connect with the railroads. He has now extended his line to Mesilla and Las Cruces, and has succeeded in effecting an arrangement with the other state companies on the route by which through tickets to St. Louis from Silver City, Mesilla, Las Cruces or El Paso are furnished at remarkably low rates.”

“Mr. Cardis has met and overcome many obstacles in bringing about this happy result, obstacles that would have dismayed and discouraged a man of less energy; and he is not only entitled to great credit, but also deserves a liberal support from the traveling public. Under the new arrangement, a person desiring to visit the east from this place can procure a through ticket to St. Louis over this route for $107.50, or a ticket to go and return for $161.25. This is a very great reduction on former rates of fare and is as low as can reasonably be expected. Speaking from personal experience we recommend the Southern route as being far superior to any other; the roads are better, frequent opportunities are afforded to obtain rest and sleep; incidental expenses are less, and the traveler in winter never suffers from the severe cold that is experienced on the northern route.”

“Mr. Cardis’ coach leaves here every Monday* morning at 7 o’clock; at mid-day cottonwood ranche is reached and the traveler can obtain a good meal and an hour’s rest. El Paso is reached the same evening; here the traveler will find good hotel accommodations, and he takes his seat at seven o’clock the next morning in one of Mr. Cardis’ elegant Four Horse Coaches and rolls out of El Paso refreshed by a full night’s sleep.”

Fort Davis – Library of Congress Photo

“Two days takes him to Fort Davis where he again lays over one night and has another opportunity to obtain a good rest, and where he will find persons who will take pleasure in administering to his wants and comfort.”

Fort Concho – Library of Congress Photo

“He starts the next morning for Fort Concho which is reached in three days. Here the traveler will again find comfortable quarters and can rely upon being well cared for. Leaving Fort Concho in a fine concord coach eh arrives at either San Antonio or Austin in two days, and there takes the rail for St. Louis, or New Orleans.”

“The traveler over this route will discover that nothing has been left undone to contribute to his comfort. He will find it to be the cheapest, the safest, the most comfortable route by which to reach the States. He will find stations, every few miles between Mesilla and the Railroad, where he can get good meals at 50 cents per meal. On the whole we recommend this route in preference to any other.”

Mesilla Valley Independent, Sept 22, 1877 (newspaper)

*Sunday

This stage line was a promise unfulfilled. 18 days after this article appeared, Cardis was murdered by Charles H. Howard, one of the many victims of the San Elizario Salt War.

“On… October 10… Cardis entered the store of E. Schutz and Brother, and asked one of the clerks to write a letter for him. He was sitting in a rocker with his back to the door when… Howard enter[ed] the front door with a double-barreled shotgun…. Cardis immediately rose, passed behind the clerk, and took a position back of the desk which concealed the upper part of his body. Howard emptied one barrel into the lower part of [Cardis’] body and legs and as the torso sank into view, the second charge of buckshot penetrated his heart.” – The Texas Rangers by Walter Prescott Webb.

On December 12, 1877, Howard went to San Elizario with a guard of Texas Rangers. They were attacked by a enraged mob demanding Howard be surrendered. On December 17, he gave himself up to the mob, which quickly organized a firing squad of Mexicans, to provide the shooters with some legal protection from American consequences:

“After they fired, Jesús Telles ran up and attempted to slash Howard’s face with a machete. He swung his weapon, but Howard twisted away, and Telles cut off two of his own toes instead. The bodies of Howard and two of his agents, also shot by the firing squad, were mutilated and dumped down an old well about a half mile away.” – Source.

A Ride You Don’t Want To Take

Stage Coach Hanging – Library of Congress Photo

Links:

Louis Cardis biography

Charles H. Howard biography

Charles H. Howard, another biography

San Elizario, Texas

San Elizario Salt War

Mesilla Stage Coach – More

Books:

The Texas Rangers, by Walter Prescott Webb

Salt Warriors: Insurgency on the Rio Grande by Paul Cool

Tags: History, Mesilla, Stage Coach, Hanging